If You Want to Better Understand Startup Communities, Read These Three Women

I’m working hard on The Startup Community Way this week with my co-author Brad Feld. As we’re polishing up the meaty part of the book—which draws on a wide range of theory, empirics, frameworks, and just some really brilliant thinking on the part of the many impressive shoulders this work stands upon—a few names keep coming up in the references we’ve assembled.

Three of these names I want to talk about today are intellectual giants in the areas of entrepreneurship, geography, and cooperative social systems. Their work collectively intersects in a way that explains a lot about why startup communities exist. If you want to understand startup communities, you should know their work. Two of them I consider friends, so not only do I get to benefit from their insightful work, I also know there’s a kindness and generosity behind their ideas. The third is not someone I knew, and sadly she’s already passed on. But, I think a lot of her work and I’ve written about it already.

All three are women.

Left to right: AnnaLee Saxenian, Maryann Feldman, Elinor Ostrom

AnnaLee Saxenian

Anno is the long-time Dean of the Information School at the University of California Berkeley. Prior to that, Anno made a name for herself as an economic geographer and regional studies researcher who studies the geography of innovation. She is one of the most important thinkers on the role of networks and organization in shaping why some regions are more innovative and entrepreneurial than others. Here are a couple of her works that you should read.

- Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Her seminal work that compares the fate of two high-tech regions in the Post-WWII War period. As late as the early-1980s, Silicon Valley and the Route 128 Corridor near Boston looked similar in terms of their ability to produce a high rate of information technology businesses. But, the Route 128 region stalled while Silicon Valley pulled further ahead in the global technology race. What explains the divergence, argues Saxenian, was the way people and businesses were organized and the culture and norms that defined both places. The rigid hierarchical structure of Boston left it flat-footed and unable to adapt to rapid technological change, while the network-based structure shaped by Silicon Valley’s open culture of collaborative competition made it better-positioned to recognize and capitalize on these changes.

- The New Argonauts: Regional Advantage in a Global Economy. In this book, Anno documents the pipeline of international talent flooding Silicon Valley for many years and links that to its success. Furthermore, she demonstrates the valuable linkages between individuals in The Valley and their home countries. These “diaspora” have played a major role in fueling the development of high-technology clusters in places such as Taiwan, Israel, China, and India, as expats from these and other places form strong networks that flow capital, ideas, talent, and know-how between The Valley and their home countries. I believe building stronger linkages with leading entrepreneurial hubs is an underutilized strategy for lagging regions.

Maryann Feldman

Maryann is a professor of finance and public policy at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Her work has been highly influential in establishing the role of social capital and leadership in systems of entrepreneurship. She is one of the most insightful thinkers on what makes some regions innovative and entrepreneurial while other similarly situated places (i.e., comparable resource endowments) are less so. Here are some papers she has authored that are fundamental to understanding this phenomenon. She has written a lot in these areas, so this list is by no means exhaustive.

- Dealmakers in Place: Social Capital Connections in Regional Entrepreneurial Economies. Maryann and her co-author Ted Zoller study “dealmakers”—highly connected individuals with deep entrepreneurial experience, fiduciary ties to startups, and valuable social capital who form the backbone of startup communities. They found that a density of dealmakers, and the connectedness between them, is more predictive of higher startup rates and a vibrant local startup community than are quantity-based measures of startups and investors. These dealmakers are the bridge-builders that make things happen, connect people, shape networks, and facilitate the flow of resources through a startup community.

- Creating a Cluster While Building a Firm: Entrepreneurs and the Formation of Industrial Clusters. Much of the conversation on entrepreneurial ecosystems is about how the external environment shapes startup outcomes. In this work, Maryann and her co-authors Johanna Francis and Janet Bercovitz flip this around—asking how entrepreneurs, as change agents, shape the environment and institutions around them. Critically, and this is a central theme to much of Feldman’s work, is a focus on the genesis of entrepreneurial clusters. Too often, people try to replicate Silicon Valley today and overlook what can be learned from its origin—focusing on efforts that lag, not lead entrepreneurial beginnings. Of course, replicating any complex system (like a startup community) is impossible, but this distinction is critical. If you are in a nascent startup community and want to learn from the Silicon Valley model, look to the past—60 years or more—not to today.

- The Character of Innovative Places: Entrepreneurial Strategy, Economic Development and Prosperity. This may be my favorite paper of all. Building on her earlier work, Feldman goes deeper on the notion of entrepreneurs as change agents who shape their environment and build institutions of support. The focus here is on entrepreneurial leadership applied to improving conditions that shape and benefit the broader community. Feldman writes: “What matters most is human agency—the building of institutions and the myriad public and private decisions that determine what I call the character of place—a spirit of authenticity, engagement, and common purpose.” This reminds me of one of the pillars of the Boulder Thesis, which Brad wrote about in Startup Communities—entrepreneurs must lead. A theme you’ll see in our upcoming book is that leadership makes all the difference.

Elinor Ostrom

Elinor Ostrom, was an American political economist, who was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. She was the first woman to receive the award. While her work isn’t directly tied to startup communities per se, her research on cooperation and collective action explains a lot about why startup communities exist and why some places do this better than others. I wrote about this concept last year, and dubbed it the Nobel Prize in Startup Communities. As I wrote then:

She challenged the notion that in the absence of a central governing authority, shared resources will be under-developed and over-utilized. Conventional thinking at the time was that our selfish human nature prevented us from cooperating in a way that would ensure sustainability of shared resources (like those in a startup community).

But Ostrom overturned this thinking. Through the use of experimental techniques and the observation of societies who relied on shared (scarce) natural resources, she demonstrated that under the right conditions, people are willing to cooperate for the greater good and engage with a positive sum mindset.

In her Nobel acceptance speech, she described her work in the following way:

“Carefully designed experimental studies in the lab have enabled us to test precise combinations of structural variables to find that isolated, anonymous individuals overharvest from common-pool resources. Simply allowing communication, or “cheap talk,” enables participants to reduce overharvesting and increase joint payoffs, contrary to game-theoretical predictions.”

Said differently, we tend to cooperate with people we know, trust, and frequently engage with. And, conversely, it’s easier to defect or play a zero sum game against people we don’t.

The central thinking behind Startup Communities is to do exactly that—to improve human relationships in a way that allows for collaboration, cooperation, and idea sharing to become second nature. This is why one of the four pillars of the Boulder Thesis—that the startup community must have continual activities—is so critical. Social cohesiveness and trust are essential for the sorts of norms and informal rules that allow collaboration to occur in a startup community. Frequent engagement allows that to develop.

This also supports another pillar of Brad’s Boulder Thesis—that of constant engagement along the entrepreneurial stack. Consistent contact builds trust, and trust is essential in entrepreneurship and building communities of support around it.

I hope you’ll have a chance to benefit from the work of these three women as I have.

Robert Noyce, Mao Zedong and Lessons for Startup Communities

In 1957, a group of eight Silicon Valley executives lead by Robert Noyce resigned from famed Shockley Semiconductor to start a rival in Fairchild Semiconductor. This sort of thing happens all the time in Silicon Valley today, but at the time, it was a watershed moment that sent reverberations throughout the industry. The Traitorous Eight, as they became known, changed the course of innovation forever by injecting the region with an entrepreneurial ethos that continues to this day, and has made Silicon Valley the envy of the world.

Around the same time, nearly 6,000 miles (~10,000 kilometers) away, a very different type of revolution was taking place in Communist China. In 1958, Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Great Leap Forward—a wide-sweeping series of economic and political reforms aimed at transitioning China from an agricultural economy to an industrialized one, and at consolidating power behind the socialist regime.

One of the first initiatives was the Four Pests Campaign, an effort to eradicate insect, rodent, and avian populations that were thought to be threatening the health and well-being of the Chinese people. Birds, in particular the tree sparrow, were the most aggressively targeted because they fed on human grain and fruit supplies. The sparrow, it was feared, would cause starvation of the Chinese people.

And, the campaign was successful—pushing the tree sparrow nearly to extinction in less than two years. The result? The disruption of a delicate ecological system that contributed to the Great Chinese Famine of 1959-1961, killing an estimated 15 to 30 million people. What went wrong?

By eradicating the tree sparrow, the government exacerbated the very problem they were trying to solve.

It turns out that not only did tree sparrows eat grains targeted for human consumption, they also fed on insects that were an even bigger drain on grain supplies. With a key predator out of the way, the insect population swelled and grain supplies collapsed, which is how the eradication of the tree sparrow contributed to widespread famine. The policy was terminated in 1960 when it became clear what a disaster it was.

So, why on earth am I linking the Great Chinese Famine with the essence of Silicon Valley’s entrepreneurial spirit and with startup communities today? Because these are important lessons in the law of unintended consequences, which are common in complex adaptive systems like startup communities.

The Chinese government took a heavy-handed, top-down approach to preserve food supplies and created a much bigger problem by not thinking systemically—unleashing a destructive feedback loop. At the same time, the Traitorous Eight took the seemingly isolated and relatively inconsequential decision of escaping a misguided (and reportedly tyrannical) William Shockley with the aim of creating something better for themselves. And yet, what it helped spark was a new way of doing business in an new technological era. It’s hard to believe their immediate plan was to transform the regional business culture—one that is now emulated globally to promote innovation-driven entrepreneurship. But that’s what happened anyway.

The lesson for startup communities is that you might not know if a proposed course of action will produce famine or feast—this can only be determined through trial and error, an informed intuition, some humility, and a desire to learn from mistakes. This is also why big ticket initiatives or programs should be considered carefully. Take a more measured approach first and see what works and what doesn’t, learn, adapt, and change course as needed. The biggest successes are often not the result of efforts at the level of “species eradication”, but rather, at the level of “let’s try doing something we’re already doing, but better.”

***

A major tip of the hat to Nicolas Colin, who during a conversation on complex systems and startup communities, alerted me to the Four Pests Campaign, which I had previously been unaware of.

Startup Communities Are Not Like Recipes, They are Like Raising Children

I’ve often heard people say “building startup communities (or startup ecosystems) is not about the ingredients, it’s about the recipe.” What they mean is that a focus on the individual people, institutions, and resources will provide only limited insight or success, and that what matters most is how these things all come together. Integration is the right concept, but a recipe is the wrong analogy.

Recipes, like chicken noodle soup or chocolate chip cookies, are simple systems. These recipes require some understanding of techniques and tools, but once learned, they are replicable with a high degree of certainty. The process of creating these “systems” can easily be broken down into constituent parts, such as chopping vegetables or sifting flour, and their integration (mixing) requires little precision.

Recipes become complicated when they involve a twenty-course tasting menu at a restaurant with three Michelin stars. Producing and serving these meals is surely a challenging problem, requiring highly specialized expertise, coordination of many factors, and consistency at scale. But these systems are also ultimately solvable, and when mastered and carried out with care, they can be replicated with relative precision. Restaurants do this repeatedly every night in cities around the world.

Startup communities and startup ecosystems are nothing like this. They are complex systems, meaning they have many “agents” (people and things), interdependencies, and are in a constant state of evolution, which makes fully wrapping your arms around them a challenging task. Most importantly, no one is in control. Such systems cannot be fully understood, predicted, controlled, or replicated; they can at best be guided and influenced. And yet, many strategies used in startup community building today still attempt to impose a complicated systems worldview onto what is an inherently complex system. This is the central problem facing startup community building in practice today and why so many well-intentioned efforts fail.

A better approach for building startup communities is not one steeped in a fixed set of ingredients, a rigid prescription of rules, and where engineered, linear processes are carefully calibrated through tight control. Instead, dealing with complex systems is best done with an informed intuition, trial and error, humility, and a desire to learn. It is more about getting the conditions right than aiming for a specific outcome. This is why you can learn more about startup community building from raising a child than you can by flawlessly executing even a complicated recipe (or system).

To drive this point home, I’m going to pull a passage from Complexity and the Art of Public Policy: Solving Society’s Problems from the Bottom Up, by the economist David Colander and physicist Roland Kupers, which I think captures this idea perfectly. (this quote has been slightly modified to improve readability where text was streamlined):

One approach to parenting is to set out a set of explicit rules for the child—”this is what you are to do; this is what is best for you, and these are the consequences of your not following the rules.” That is the idealized “control approach” to parenting.

There are two problems with this—the first is that most parents are not sure which rules are the correct ones. If they pick the wrong ones, then the child’s welfare won’t be maximized. The second problem is that the child may not follow the rules—do you then give in or not?

The true alternative to top-down control parenting is the parenting equivalent of the complexity approach we are advocating; a laissez-faire activist approach. In a laissez-faire activist approach you have as few direct rigorously specified rules as possible. Instead, you have general guidelines, and you consciously attempt to influence the child’s development so he or she becomes the best human being possible.

Instead of focusing on the rules, the focus of complexity parenting is more on creating voluntary guidelines, and providing a positive role model. (emphasis added).

This is why, in my upcoming book with Brad Feld, The Startup Community Way, we’ll be talking a lot about the behaviors, attitudes, and leadership qualities that promote healthy startup communities, and not about ingredients or recipes. We understand that startup communities require a different set of guidance, tools, and techniques than most of us are used to applying in our professional lives (which occurs because most workplaces are structured in a top-down, hierarchical way).

But the reality is, we all deal with complex systems everyday—from cities to our bodies to any situation that involves interacting with other people. Complexity is all around us. Our hope is that we’ll do our part to help you uncover how to apply what you already know to a different type of problem: that of building a vibrant startup communities in the city where you live. We can’t wait to share our ideas with you.

New Evidence on Fostering Productive Startup Communities

Last week, Endeavor Insight (the research arm of Endeavor Global) teamed up with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to publish a new report on fostering productive startup communities. The report was authored by Rhett Morris and Lili Török of Endeavor, and I think it is one of the best pieces of empirical work I’ve ever seen on startup communities.

Why such a strong endorsement? Because it helps fill a pretty big information gap for two of the most important principles for building startup communities—networks over hierarchies and entrepreneurs as leaders. At present, the evidence-base is thin, due to the fact that there are no shortcuts to doing this type of work well (building network maps with vital information about the nodes and relationships among them)—it requires painstaking, on-the-ground data collection, which is expensive to do and requires a lot of time (it took Endeavor 18 months to complete the study). Thankfully, Endeavor has done the work in two cities so that we can all learn from it, and more importantly, use to help persuasively state the case for bottom-up community-building.

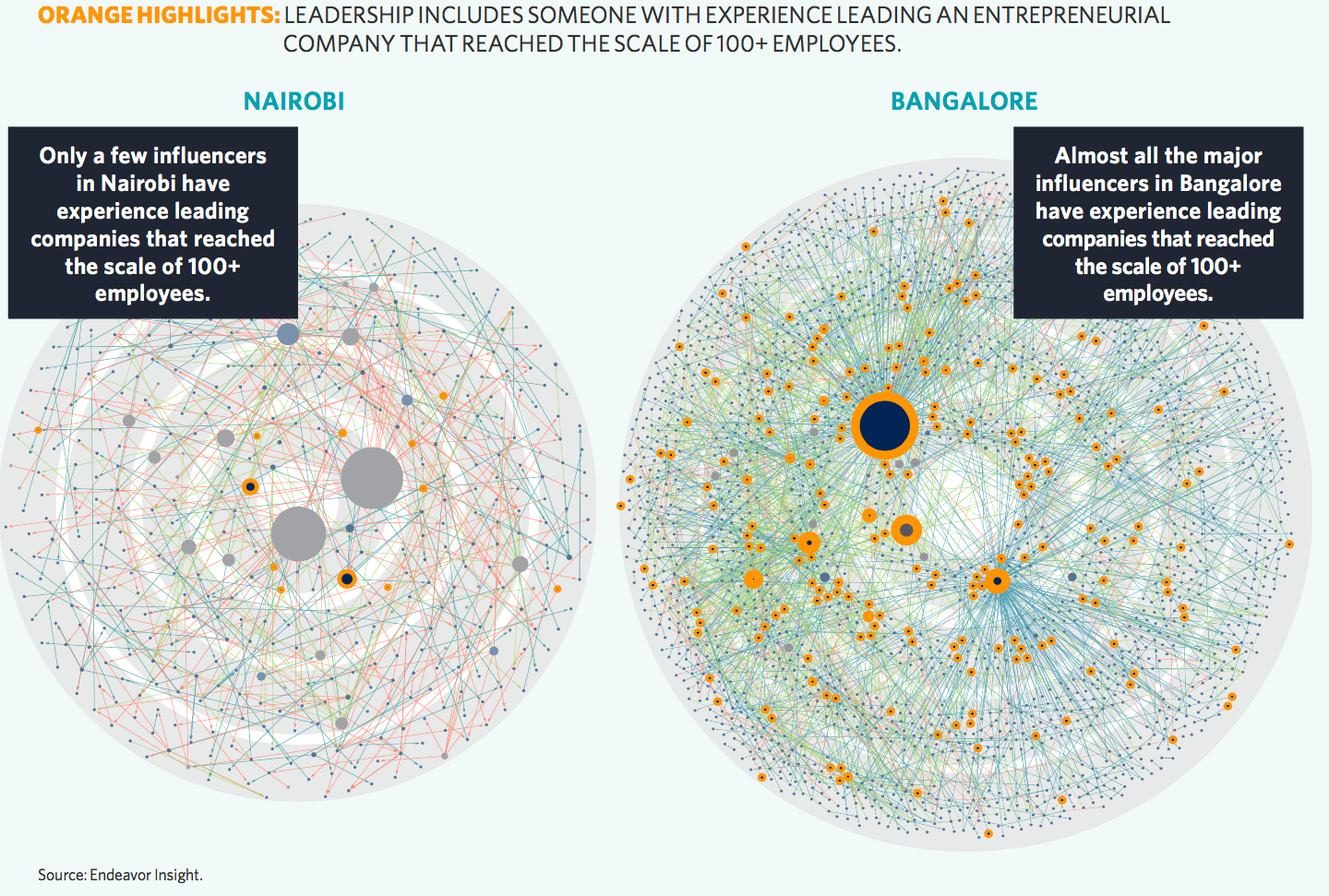

The research takes a case study approach, studying in extensive detail the startup community networks in Nairobi and Bangalore. To do this, the authors collected information on the individuals and organizations involved in the startup communities in each of these two cities, and mapped the relationships among them. The main result: Bangalore’s startup community is more productive (more high-growth firms and companies at scale) because the network is denser and because the biggest influencers are themselves entrepreneurs; the opposite is true in Nairobi.

***

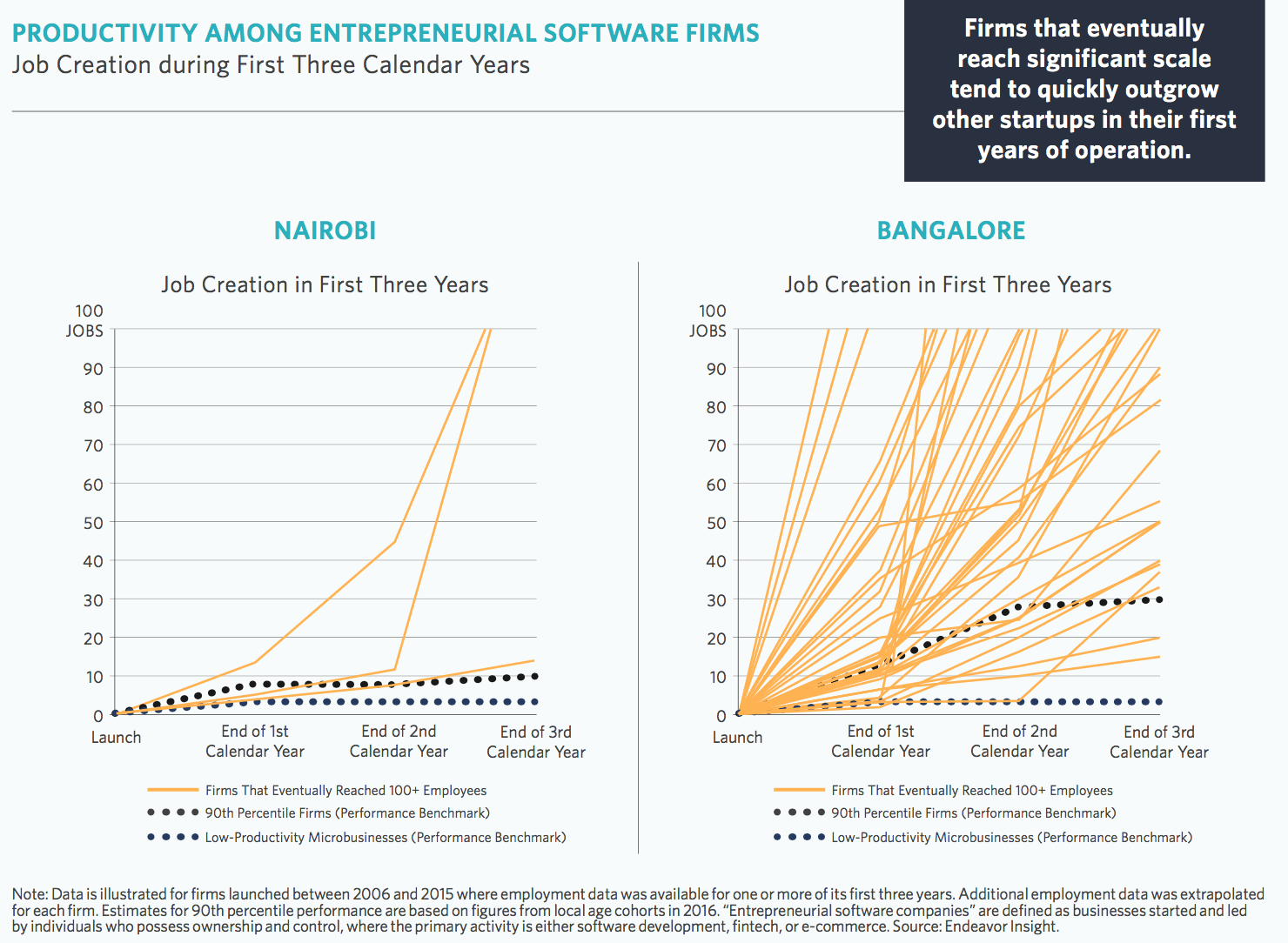

The report begins by setting context on the importance of entrepreneurship, by demonstrating that a relatively small number of high-growth companies create most economic value in jobs. This is true in most countries and cities, and as we can see here from the report, is more the case in Bangalore versus Nairobi.

In other words, most businesses don’t produce much in the way of jobs or output, but a small number create a lot of those things, and they drive economic growth. Displayed differently, the report shows that Bangalore’s high-growth business sector is much more productive than is Nairobi’s.

In other words, Bangalore has been better at producing businesses that achieve very high rates of growth and reach a large scale.

That of course leads to the question of why in one city but not the other? There are a number of factors that could affect this, but central to this study—and two in which I mentioned before are often neglected due to measurement challenges—are networks (relationships) and leadership.

More specifically, Nairobi not only lacks the network density of Bangalore, but it critically lacks the right type of influencers. As the network graphs below make clear, the most influential people in the Bangalore startup community are successful entrepreneurs—those that have guided companies to scale—and non-entrepreneurs are not very influential. In Nairobi, the opposite is true.

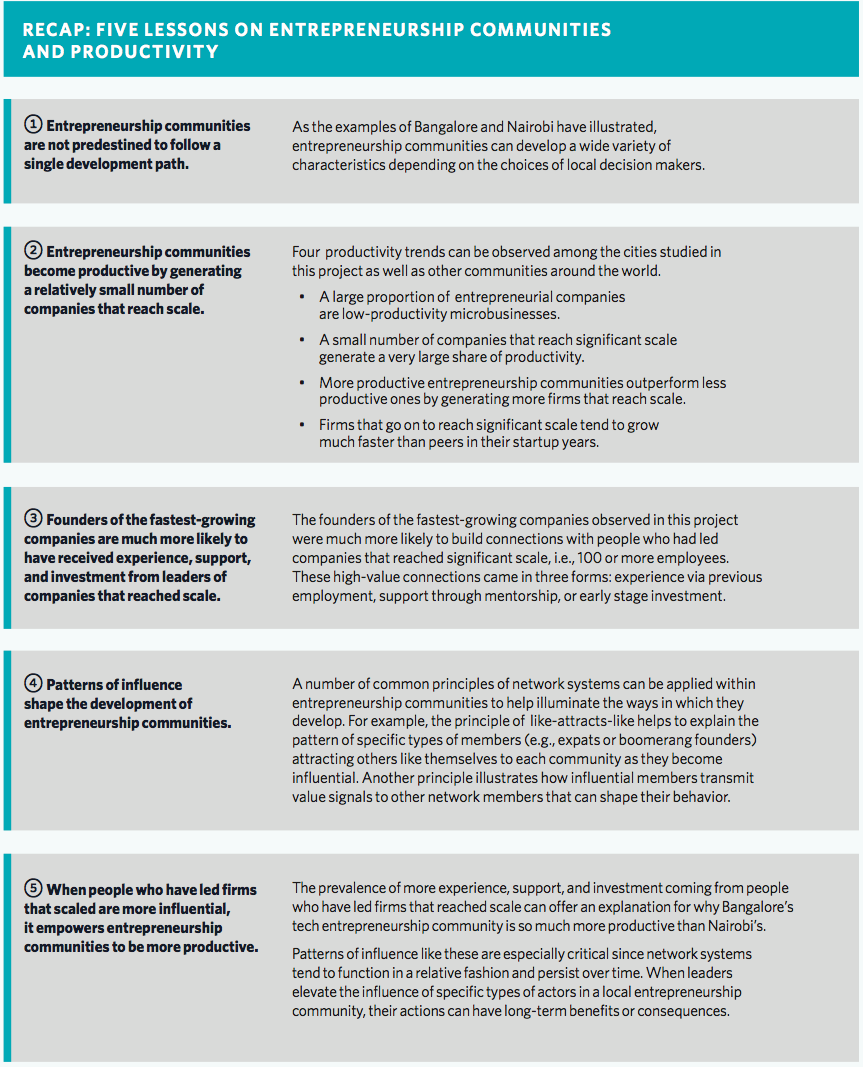

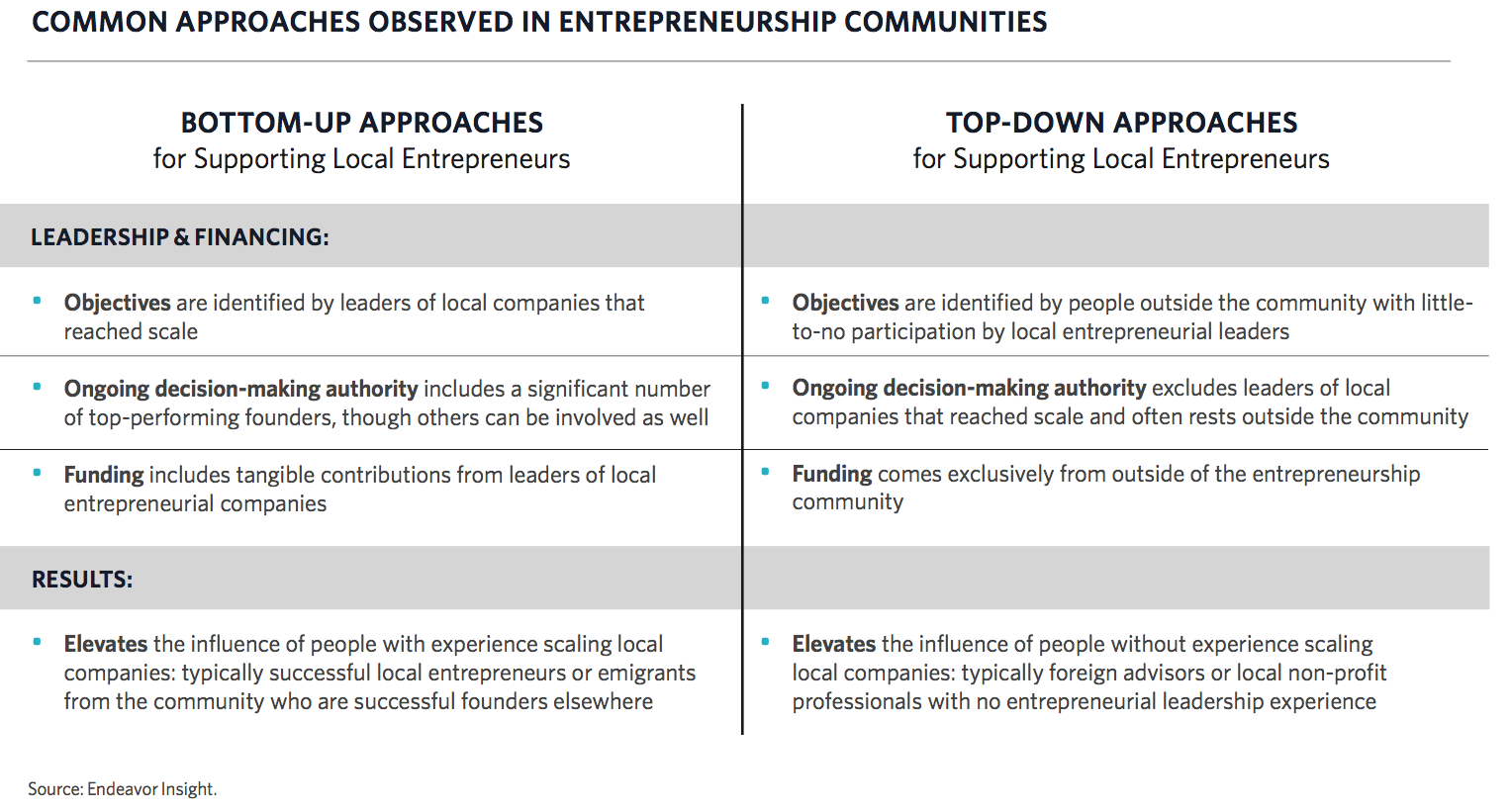

Pretty impressive right? I encourage you all to read the report itself—it’s not too long and it’s written very well (succinct yet weighty). The report summarizes the following five findings, followed by a graph explaining the differences between on bottom-up, network-based approaches to startup community building (recommended) versus top-down ones (not recommended).

Finally, the report concludes with some recommendations, which I’ll spell out here.

- Avoid the myths of quantity (ie, quality over quantity any day—something I call the More of Everything Problem)

- Follow local founders who have reached scale

- Listen to leaders of the fastest-growing firms to identify the most critical constraints in the local entrepreneurship community

- Expand existing mechanisms that leaders of companies at scale use to influence upcoming founders

- Invite leaders of companies at scale to positions of influence at existing support organizations

Couldn’t agree with that more. Well done, Rhett, Lili, and your team.

Startup Communities are Like That Middle School Dance – Awkward!

Creating meaningful connections can be difficult at any age.

You remember how you felt in 7th grade at the dance with the girls clustered in groups on one side and the boys clustered in groups on the other side of the gym? Even the most confident still had a strong sense of fear of what was going to transpire next. They just hid it better.

The basis of that fear – a fundamental fear of the unknown. What do we say? (I don’t want to look stupid.) What is the first move? (Should I ask her to dance or just talk to her.) Who should I approach? (The girl that I like or the girl that keeps looking at me.)

The sheer memory of that night (my memories might have lasted until college, by-the-way) remains close to the surface as adult events many times evoke the same awkward set of questions and unknown answers.

Nascent startup communities are often like those middle school dances where there is awkwardness around what to say and who to talk to.

Entrepreneurs feel awkward talking to government officials. (Do we have anything in common?) Corporate executives feel awkward revealing departmental vision to entrepreneurs. (Fear that the startup might steal something.) Investors are always walking a tight rope. (Let’s not disclose what deals we are doing or about to do.)

The result of this awkwardness are communication silo’s that prohibit healthy connections to flourish. It is clear that many communities exhibit clusters of like-minded people that are not connected to others in their community. This is a big problem. Why?

The secret sauce of the mother-of-all communities (Silicon Valley) is the ability to quickly and effortlessly connect with the resources needed to start and grow a company. The valley is the quintessential flat network. This was mapped excellently in the work that Zoller & Feldman did around dealmakers in their research of 12 US cities in 2012.

One of our community-development principles here at Techstars is that emerging or nascent startup communities can advance quicker when they work to connect their clusters. Sometimes local dealmakers can make this happen. Sometimes an outsider has to facilitate these connections.

Bottom line – startup communities can’t advance at the dance unless everyone starts dancing together.

Startup Communities Revisited

Writing a book is a very hard thing. It’s one of the hardest things I’ve done professionally. It is the nonlinearity of the process that makes it so difficult and the sheer perseverance that’s required. It’s remarkable to see how different the content is today compared with where it was on day one.

Part of the process means writing a lot of words that no one will ever see. I have written literally tens of thousands of words—several complete chapters even—that will never see the light of day. I was going through one of those today and decided I will publish it here. It is a brief summary of Brad‘s book Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City, meant to be a refresher for those familiar with the material and to quickly get newcomers up to speed. I also added layers of my own context, data points, and interpretation.

And with that, at the risk of depriving Brad of some royalties and pissing off his publisher, here is my condensed version of Startup Communities.

***

We know that you read Startup Communities (“SC1”) on more than one occasion and handed it out at your office summer party. But, in case you are forgetful or your mother-in-law wants to better understand what you do for a living without having to miss out on her tennis match later, in this chapter we revisit the main themes of SC1 and provide a concise guide for newcomers to get up to speed.

This chapter is not a substitute for actually reading SC1 (which you should do), though we think you can grasp many of the high-level concepts here quickly. If you have already mastered the content in SC1, feel free to skim through this chapter to refresh your memory or go a bit deeper in certain areas, even referring back to the first book as you go along—perhaps you’ll see something in a different way this time.

ABOUT BOULDER

Boulder made for an exemplar case study in SC1 for three reasons. First, it is a vibrant and sustainable startup community. Second, it is unlike other leading startup hubs, such as Silicon Valley, San Francisco, Boston, and New York. Finally, Brad has lived in Boulder since 1995 and has been actively engaged with its development—giving him an intimate view of the internal dynamics of the startup community there.

Boulder has some defining characteristics.

Boulder is a small city. With a resident population of approximately 108,000 and a broader metropolitan area of more than 322,000 people, Boulder is just the 155th largest metro area in the United States and the 4th largest in the State of Colorado. In terms of population density (inhabitants per square mile), Boulder ranks 64th nationwide, and is one of the most densely populated mid-size metropolitan areas in America.

Boulder is a smart city. The University of Colorado Boulder is a major research institution of more than 37,000 students, faculty, and staff situated near the center of town. Boulder hosts three national labs, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and has the highest concentration of adults with advanced degrees among large- and mid-size U.S. metropolitan areas.

Boulder is an innovative city. According to a 2013 Brookings Institution study, Boulder ranked 33rd among US metro areas in terms of patenting activity between 2007-2011, but ranked sixth when scaling for the size of the workforce. Similarly, venture capital investment in the Boulder metro area ranked 16th nationally in 2016-17, but when adjusted by the size of the community, it ranks third—behind only San Francisco and San Jose (Silicon Valley). Google will soon open a new 330,000 square foot campus near downtown Boulder that will employ 1,500 people.

Boulder is an entrepreneurial city. A Brookings Institution study of the fastest growing firms in the United States ranked Boulder first on a per-capita basis, while a joint report by Kauffman and Engine found that Boulder leads the nation in high-tech “startup density,” and by a long shot too—at more than six times the national average. The overall rate of new business formation places Boulder among the top ten percent of major metros nationally. Livability, a website that ranks quality of life factors in small and medium sized cities, recently rated Boulder as the best city in America for entrepreneurs.

Boulder is an attractive city. With nearly 250 predominantly sunny days per year (no, it’s not 300 as popular legend states), Boulder is among the sunniest cities in America. Its access to the Rocky mountains attracts adventure-seekers, and a plethora of high-end restaurants, shopping, and entertainment, gives the young and active plenty to do. Richard Florida, an urbanist, ranks the Boulder metro fifth for concentration of workers in the “creative economy”—meaning that Boulder is home to not just techies, scientists, and other highly skilled professionals, but also plenty of artists, musicians, and other creative types that help feed an innovative, dynamic, and vibrant economic system.

Having these factors is a major advantage for Boulder’s startup community—brains, capital, a knack for innovation, an entrepreneurial spirit, and an exciting, thriving place to live are critical factors for creating and sustaining a vibrant startup ecosystem. But, they alone are not enough. Many cities have smart people, innovative activity, a density of startups, and an array of amenities, but lack the entrepreneurial vigor of Boulder. The difference lies in the way these ingredients are mixed together, primarily by means of human relationship. The difference is culture and social norms. That’s what startup communities is fundamentally about.

THE BOULDER THESIS

The main intellectual novelty of SC1 is the Boulder Thesis—a framework that explains why a small city of just over 105,000 residents is able to consistently produce a steady drumbeat of high-impact startups. More specifically, when looking at the leading startup hubs in the United States and globally, Boulder doesn’t look like the others—even among well-educated cities with universities, flagship companies, and attractive amenities. Something about Boulder is different. Woven into the fabric of the Boulder startup community is a way of combining these inputs that has given fledgling companies there a better chance of success. That has been distilled into the Boulder Thesis. It has four key components:

Entrepreneurs must lead the startup community. Although a range of participants are critical to a startup community—including government, universities, investors, mentors, and service providers—the entrepreneurs must lead organizing efforts. Entrepreneurs here are defined as those who have founded or co-founded a growth-oriented startup.

The leaders must have a long-term commitment. Entrepreneurs must be committed to building and maintaining a startup community over the long-term. Leaders should take at least a twenty-year view—a view that refreshes every year (the horizon is always twenty years out). For a startup community to be lasting, it must be bigger than the latest fad or as a response to an economic downturn.

The startup community must be inclusive. Startup communities should embrace a philosophy of extreme inclusion. Anyone who wants to get involved should be able to, whether they are new to town or new to startups, or whether they are company founders, employees, or simply want to help out. A startup community that embraces diversity and openness is a more flexible, adaptable, and resilient startup community.

The startup community must have continual activities. It’s important that the span of participants in a startup community are constantly engaging—not through passive events like cocktail parties or award ceremonies, but through “catalytic” events like hackathons, meetups, open coffee clubs, startup weekends, or mentor-driven accelerators, which are venues for tangible, focused, engagement among members of the startup community.

THE IMPORTANCE OF GEOGRAPHY

A dense co-location of businesses is valuable for many sectors of the economy, because it lowers transaction costs and improves matching between firms, labor, suppliers, and customers. These “agglomeration effects” or “external economies” (economies of scale that exist outside the firm, often at the local or regional level) are particularly important in industries where specialized inputs and highly-skilled workers are important to production (a “bigger pool” of resources to draw from).

Beyond lowering transaction costs and improved matching, a third benefit to density is vital to innovation and entrepreneurship—a concept economists refer to as “knowledge spillovers,” or the exchange of ideas. In complex activities like starting and scaling innovative businesses, idea exchange and learning from others is critical. Because complex concepts are difficult to transfer verbally or in writing, learning of this nature is best done at an arm’s length (“learning by doing” or “learning by seeing”).

Brad has written on his Feld Thoughts blog (www.feld.com) about the phenomenon of startup density and the importance of density to entrepreneurial performance. As one example, he describes that when doing business in well-known startup hubs like San Francisco or New York, he tends to stay in a relatively confined area. This is particularly true in Boulder, where most of the startup activity is concentrated in a relatively confined space of about 40 square blocks.

Academic research confirms that measuring startup density at the level of cities or metropolitan areas is probably not fine enough, having established a high “decay rate” of knowledge sharing over distances. One study found that the benefits of knowledge sharing in the software industry, for example, are ten times greater when co-locating within one mile of similar companies versus within two-to-five miles. Another study found that the benefits of co-location among advertising agencies in Manhattan were fully depleted after just 750 meters.

To quote Maryann Feldman, an expert on the geography of innovation:

“…geography provides a platform to organize resources toward a specific purpose. While firms are one well-known way to organize resources, location provides a viable alternative—a platform to organize economic activity and human creativity… More than facilitating face-to-face interaction and the exchange of tacit knowledge, geography enhances the probability for serendipity—the chance for something unexpected to have a profound and transformative impact.”

Visionaries like Steve Jobs understood this, which is why he designed the Pixar office in a way that would force “spontaneous collisions” among colleagues from different disciplines. Google, Facebook, and other highly innovative companies have followed suit. They don’t provide free food and table tennis for nothing, and it’s not just to give overworked engineers a fun way to destress—it’s to get people who might not otherwise engage with one another to open up, share ideas, and find new ways to collaborate.

NETWORKS OVER HIERARCHIES

Advanced and emerging economies alike have been undergoing a massive transformation in recent decades, from centralized, command-and-control structures of the industrial era, to decentralized, network-centric organizational forms of the information age.

Hierarchies are best suited for conditions that require tight control of production or information, such as manufacturing facilities or in large bureaucracies (universities, government). Hierarchies require formal rules and standard operating procedures. Networks, on the other hand, require flexibility and horizontal flows of information. Startup communities rely upon unencumbered information flows and therefore thrive in network structures such as these. Conversely, they die under hierarchical control.

This thinking, and Brad’s writing about it in SC1, is heavily influenced by the Berkeley economic geographer AnnaLee “Anno” Saxenian, in her seminal work Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. This book is probably the most important book ever written on how to think about what makes some regions consistently more innovative and entrepreneurial compared with others.

In her work, Saxenian compared two technology hubs—California’s Silicon Valley and the Route 128 Corridor near Boston—that looked similar as late as the mid-1980s in terms of their ability to produce a high rate of information technology businesses. From there, however, the Route 128 region spiraled into a state of deep decline while Silicon Valley pulled further ahead in the global technology race. What changed? A period of intense, rapid technological disruption and increased global competition left the more rigid hierarchical structure of Boston flat-footed and unable to quickly adapt, whereas the network-based structure shaped by Silicon Valley’s open culture of “collaborative competition” made it better-positioned to capitalize on these changes.

As Brad summarized in the first book:

“Saxenian persuasively argues that a culture of openness and information exchange fueled Silicon Valley’s ascent over Route 128. This argument is tied to network effects, which are better leveraged by a community with a culture of information sharing across companies and industries. Saxenian observed that the porous boundaries between Silicon Valley companies, such as Sun Microsystems and HP, stood in stark contrast to the closed-loop and autarkic companies of Route 128, such as DEC and Apollo. More broadly, Silicon Valley culture embraced a horizontal exchange of information across and between companies. Rapid technological disruption played perfectly to Silicon Valley’s culture of open information exchange and labor mobility. As technology quickly changed, the Silicon Valley companies were better positioned to share information, adopt new trends, leverage innovation, and nimbly respond to new conditions. Meanwhile, vertical integration and closed systems disadvantaged many Route 128 companies during periods of technological upheaval.”

We’ll go deeper on networks throughout the rest of the book, but the important point here is that startup communities thrive in environments where information, talent, and capital flow freely and horizontally through relational networks.

ATTRIBUTES OF LEADERSHIP IN A STARTUP COMMUNITY

SC1 listed four key attributes of leadership in a startup community. In the vernacular of the Ten Commandments, these can be thought of as the “dos” of the startup community.

Be inclusive. Leaders of the startup community should embrace anyone who wants to engage, regardless of experience, background, education, gender, ethnicity, perspective, and so on. Startup community leaders serve as gatekeepers, and have a duty to ensure the door is open to anyone. As a common point of first contact, leaders should introduce newcomers or visitors to high-impact, easy-to-access events and a handful or two of key individuals. Finally, leaders should nurture and make room for the next generation of leaders—eventually handing off existing activities, and taking on new responsibilities.

Play a non-zero-sum game. Many approach human and business relationships as a zero-sum game—there are winners and there are losers. This thinking has no business in a startup community. Participants must fully embrace the notion of increasing returns—everyone gains more by contributing positively to the collective.

Be mentorship driven. Give to others. A good mentor has no expectations of what he or she will get out of it—instead, they approach it with a “give before you get” dynamic, with a willingness to let the relationship evolve naturally. Leaders, in particular, must embrace the mentorship role, and build time for it into their regular activities. This should occur on three levels—mentoring future leaders, mentoring other entrepreneurs, and mentoring each other. Finally, lead by example.

Have porous boundaries. The best startup communities know that it’s beneficial to be open—leaders should talk with one another other, sharing strategies, relationships, ideas, and resources. Individuals who come and go should be embraced and welcomed back when they return.

CLASSICAL PROBLEMS IN A STARTUP COMMUNITY

Continuing with the Ten Commandments theme, SC1 listed ten common problems that occur in a startup community—these are the “don’ts”.

Patriarch problem. Also known as the rich old guy problem, this occurs when people try to control the startup community, restricting rather than enabling the next generation of leaders. In these controlled environments, it matters who you know, not what you know. If we haven’t said it enough before, we’ll say it again—startup communities thrive in networks, not hierarchies. To get around patriarchs, entrepreneurs should play the long game (wait for them to die off) or simply ignore them.

Complaining about funding. There will always be an imbalance between the supply of capital and the demand for it. Some local initiatives can improve things on the margin, but the underlying problem persists. At the very least, complaining about it won’t help. Instead, entrepreneurs should concentrate on something they can control—building a great business around a problem they are obsessed about solving.

Being too reliant on government. Relying on government to either lead or provide key resources for building a startup community is a misguided view over the long term. In spite of some successful efforts and the best of intentions, governments generally lack the resources, expertise, mindset, and sense of urgency to effectively mobilize resources that entrepreneurs need most.

Making short term commitments. It takes a long period of hard work to get a healthy startup community up and running in a sustainable way—at least a generation of effort (twenty-year view). Strategies rooted in the current economic cycle, political calendar, or latest trend aren’t sufficient to achieve this. And while we’re at it, this generational clock resets every year—leaders should always have a twenty-year view.

Having bias against newbies. Vibrant startup communities, like Boulder, welcome newcomers and visitors with open arms. Shunning “outsiders” or demanding that newbies “earn their way” into the startup community is a dumb, outmoded way of thinking. It is the thinking of hierarchies. Startup communities are not hierarchies.

Attempt by a feeder to control the community. In some cases, non-entrepreneurs (“feeders”) masquerade as leaders or try to control the startup community—this stifles both short- and long-term growth. Venture capitalists, governments, and universities are some of the worst offenders of this principle. It is no coincidence that many of these also operate in a hierarchy, where top-down control is a natural force.

Creating artificial geographic boundaries. Within cities, multiple startup communities can exist. For example, in the Boston metro area there are several: in Boston, there is the Financial District, Innovation District, and South End, and in Cambridge there is Kendall, Central, and Harvard Squares. Ideas do not flow in a linear fashion, and efforts to confine them to arbitrary administrative boundaries impede them.

Playing a zero-sum game. See earlier—playing a zero-sum game isn’t helpful for startup communities, including when competing against neighboring communities for the sake of promoting your own. Instead, take a network-based approach and connect your startup community with neighboring ones. Learn from each other. Share ideas.

Having a culture of risk aversion. Persistent risk aversion is another obstacle to startup community development. It typically manifests in two forms: (1) a concern about investing time in something that doesn’t end up having an impact, and (2) the fear of rejection by other people in the startup community. Take more chances, though with a view towards adjusting when feedback dictates a change in strategy. As for the fear of rejection, let it go.

Avoiding people because of past failure. A great deal of learning occurs in failed ventures. And outside of doing something seriously wrong or illegal, failed entrepreneurs shouldn’t be ostracized from the startup community. Rather, embracing them will encourage others to take risks, eventually changing the culture over time.

THE POWER OF THE COMMUNITY

Throughout the Boulder startup community, there exists a widely held set of beliefs about how to behave and interact with each other that evolved organically over time. Collectively, they are the glue that sustains the startup community in Boulder.

Give before you get. One of the secrets to success in life is to give before you get. This is particularly important in the context of a community. By investing time and energy into the startup community upfront without having an expectation of what’s in it for you personally, you will end up receiving more out of it than you put into it.

Everyone is a mentor. One of the best ways to help your startup community is to find someone to mentor. Focus on your specific skill or expertise, and let it be known that you are available to mentor someone in that area. Creating a culture of sharing knowledge is vital to a startup community, and over time, mentors may end up learning more from the mentees.

Embrace weirdness. About his theory of “creative capital,” urbanist Richard Florida once stated: “You cannot get a technologically innovative place unless it’s open to weirdness, eccentricity and difference.” Plus one to that. In Boulder, you don’t have to look, dress, or act a certain way to be accepted—you can just be yourself. And yes, you can even be weird.

Be open to any idea. The best way to learn something is to try something. In a startup, that might mean experimentation and modification, as in the Lean Startup methodology that has been popularized by Eric Ries. In a hierarchy, when something new is proposed, people try to figure out all of the ways it won’t work. In a startup community, they do the opposite. Learn how to fail fast—try something, learn from it, and make the needed adjustments, including winding it down. The bottom line though: you won’t know if you don’t try first.

Be honest. Be intellectually honest with others—do not bullshit each other. Always express yourself honestly—acknowledging that you could in fact be wrong—but do so with respect and kindness. Do this even in situations that are heated or emotional. Do this especially in those situations. Also understand your surroundings, and people give and receive feedback differently.

Go for a walk. Whenever you have something serious to talk about with someone, do so while going for a walk. Or do so riding a bike. The point is: get out from behind your desk to have some of your biggest discussions, get some fresh air, and hopefully, sunshine.

The importance of the after party. Often after major startup events, there is an after-party. Try to attend these as much as possible, engaging with individuals more deeply. The point here isn’t the after party itself, it’s that community is what the startup community is all about.

MYTHS ABOUT STARTUP COMMUNITIES

In SC1, Brad drew upon the help of Paul Kedrosky to dispel and expand upon some persistent myths about startup communities. Here are three of them:

We need to be more like Silicon Valley. No you don’t. You aren’t Silicon Valley and you never will be. Nor should you want to be. Even Silicon Valley couldn’t recreate itself if it tried. The allure of “being like Silicon Valley” is that it has many of the measurables that any startup community would want—lots of smart and creative people, an abundance of venture capital, leading research universities, great climate and amenities, an army of hot young technology startups, and a number of very large, successful companies. But what makes Silicon Valley unique lies under the surface, such as the porous boundaries of firms and institutions, the constant cycle of talent into and out of companies, and an attitude that embraces the challenges of growing and scaling young businesses. Instead, learn the important lessons from Silicon Valley and determine how they apply to your community.

We need more local venture capital. As discussed before, demand for venture capital will always exceed supply. This is a structural feature of startup communities. However, the mistake occurs with people equate the two—startup communities are bigger than venture capital. In Paul’s words:

“Venture capital is a service function, not materially different from accounting, law, or insurance. It is a type of organization that services existing businesses, not one that causes such companies to exist in the first place. While businesses need capital, it is not the capital that creates the business. Pretending otherwise is reversing the causality in a dangerous way.”

Additionally, venture capital firms needn’t exist in your community for the funds to flow in. VCs screen thousands of companies per year, and if yours is one of the good ones, they will come to you. Finally, it’s important to remember that fewer than 0.5 percent of American businesses receive venture capital funding. Many startups, even those that achieve high growth or high impact, rely on more traditional forms of financing—friends, family, savings, or the very best way, their own customers. Venture capital is a huge bonus to a startup community, but it is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for one to exist.

Angel investors must be organized. While there are many examples of some effective angel investor groups, there are many more of them that are a giant waste of everyone’s time. Many of these groups are slow, and too cautious to actually write checks to entrepreneurs—even after multiple meetings and endless due diligence. A key goal for an angel group should be to build a network of trusted co-investors. Regardless, a more direct path for angels likely occurs through interpersonal relationships based on trust, building out the broader startup community network, and ultimately, making investments in promising startups.

WRAP-UP

A quick look through the breadth of themes covered in SC1 points to some high-level areas of priority—namely, a focus on the nature of human relationships, of altruism and decent behavior to one another, of fairness, and of the way in which all of the various people and institutions in a startup community come together as being key differentiators for its vibrancy, rather than for the existence of the factors themselves. This is something we will revisit over and over again in the pages that follow, as we build on these and other themes contained in SC1—and add to them. This chapter sets the tone for our thinking about what matters most in startup communities.

Some additional topics covered in SC1 were not explicitly mentioned above—namely, the role of startup accelerators, universities, and governments. We dedicate entire chapters to each of these three topics later in the book.

This article originally appeared on the Ian Hathaway Blog.

America’s Rising Startup Communities

Last week I published a report with the Center for American Entrepreneurship that analyzed the geography of venture capital first financings across U.S. metropolitan areas during the last eight years. You should definitely check out the full study on the CAE website because it includes a lot of interesting data and graphics. You should also check out this Twitter thread I posted on the day the study was released.

Thread on the geography of first rounds of venture capital in the U.S. below. TL;DR a nuanced story, but one I choose to view (mostly) optimistically. Full analysis here: https://t.co/ymnkj4WPVv >> pic.twitter.com/43sprXFgOY

— Ian Hathaway (@IanHathaway) July 31, 2018

Here, I provide a brief overview of the main takeaways from the study. I also include an interactive map that allows users to play with some of the data. The report finds:

- After a stellar five-year period of expansion between 2009 and 2014, a sharp contraction in the number of startups raising a first round of venture capital has occurred the last three years

- This contraction has been geographically widespread—fewer metro areas had a startup that raised a first round of venture funding and those that did had a smaller number of them.

- First financings are still highly concentrated among a small number of cities—in 2016-17, five metros captured 54 percent of all U.S. first financings and ten metro areas accounted for 68 percent.

- But, a number of startup communities continue to expand—including Boulder, Columbus, Indianapolis, Charlotte, Denver, and Durham-Chapel Hill, while others exhibited relative rises (including Madison, San Diego, Pittsburgh, Raleigh, Houston, Baltimore, Seattle, Ann Arbor, Honolulu, Philadelphia, and Santa Barbara).

- The longer arc tells a more positive story—the number of startups receiving a first round of venture capital in 2017 was still 84 percent higher than in 2009, and 38 percent of metros saw an increase in deals over this period.

Some may point to conflicting evidence about the emergence of new startup hubs in the U.S., but I believe this is still a mostly positive story—more startups in more cities are accessing venture capital compared with a decade ago, a brief period of over-exuberance is moderating, and the early-stage funding market seems to be moving toward a more stable yet geographically inclusive path forward.

But that statement is not boundless—there is critical nuance. The data are a stark reminder that startup communities take time to develop, that progress will be non-linear, and that the scope could be narrower than many would hope for. History suggests that the establishment of startup hubs must be thought of in terms of decades, not years, and there are limits to the number of cities that will ultimately emerge. It is still being determined which those will be, but the overall trend points to there being more of them.

The New York Yankees and Startup Communities

Startup Communities and Saturday Morning Coffee

A recent article in 5280 Magazine caught my attention. It profiled the economic vitality of the Boulder-Denver region, dubbing it “The Most Exciting and Innovative Tech Hub in the Country.” While I expect every local publication to champion its own hometown, this one happens to be on stronger footing than most others. You see, at least in terms of innovation and startup activity, Boulder is unique among its peers.

The article—which is excellent by the way—couldn’t have come at a better time for me personally. A few days ago, I moved myself and my family to Boulder to work on a book about startup communities. Not only did I come here to work closely with my friend and co-author Brad Feld, I also wanted to experience first-hand what makes this place so special. I came here to learn… and to contribute.

Boulder may be small, but it is mighty. My own research demonstrates that Boulder is a major outlier among American cities when taking into account population size: it has the highest density of technology startups in the country (by a long shot) and it has the second highest concentration of venture capital dollars invested behind the San Francisco-Silicon Valley region. This research is a few years old, but more recent figures confirm the trend.

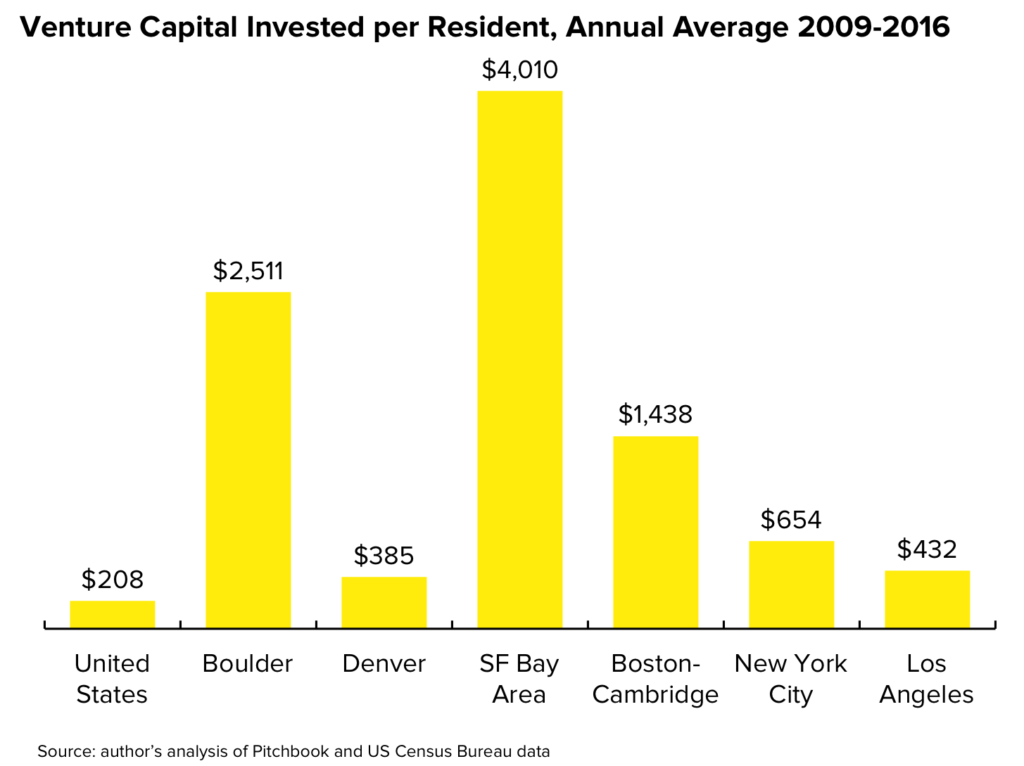

As the chart above shows, when adjusting for city population size, Boulder has more than 10 times the average for the entire United States—second only to San Francisco-Silicon Valley, which has about 20 times the US overall. Boulder’s venture capital investment per resident far exceeds that of Boston-Cambridge, New York City, and Los Angeles.

As the chart above shows, when adjusting for city population size, Boulder has more than 10 times the average for the entire United States—second only to San Francisco-Silicon Valley, which has about 20 times the US overall. Boulder’s venture capital investment per resident far exceeds that of Boston-Cambridge, New York City, and Los Angeles.

Critics may suggest that per-capita figures are misleading, and that what really matters is critical mass. It is true that Boulder is small—with approximately 108,000 residents in the city itself, and about 322,000 in the broader metropolitan area, it is most similar in size to South Bend and Green Bay. And, in absolute terms, Boulder accounted for just 1.2 percent of total venture capital invested in the United States between 2009-2016. By comparison, Denver’s contribution was 1.6 percent and San Francisco-Silicon Valley’s was 40 percent.

But, Boulder’s undeniable successes dispel those critiques. Google and Twitter acquired local startups SketchUp and Gnip, and both maintain sizable (and growing) outposts here. Biotech firms Clovis Oncology and Nivalis Therapeutics each raised north of $100M in capital on their way to public listings on the NASDAQ. SendGrid was founded in Boulder in 2009, and although the company moved headquarters to Denver last year, most of its growth—the company employs around 400 people today—occurred in Boulder. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

So, what makes Boulder so special?

To start with, Boulder has some obvious natural advantages. It is a beautiful place to live, has copious amounts of sunshine, and a vibe that attracts people who are active, mobile, and educated. It has a major research university and hosts an array of public and private R&D facilities. Historically, Boulder has boasted flagship companies in data storage, pharmaceuticals, and natural foods, which spawned a number of startups in these areas.

However, many places have some or all of those resources, yet lag behind Boulder. In fact, research has shown that the average relationship (correlation) between these factors and local high-tech or high-growth startup activity is tenuous—cities that are startup hubs have most or all of these qualities, but not all cities that have most or all of these qualities are startup hubs. In other words, these “assets,” as I will call them, are necessary but not sufficient conditions for a dynamic startup ecosystem.

If it’s not hard assets that make the difference, then what does?

In her seminal work, Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, AnnaLee Saxenian demonstrated that the differentiating factor for Silicon Valley’s success was culture. Silicon Valley firms and institutions had porous boundaries, engineers and entrepreneurs cooperated in a system that valued technological progress over firm identity, and the region embodied a flat, network-based approach to innovation and “collaborative competition.” It wasn’t just the quantity nor the quality of individual actors in Silicon Valley that decided its fate—though both were necessary—but instead, it was the way in which they engaged with each other and with the system as a whole that made the difference.

Brad’s 2012 book Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City, which this blog is largely a dedication to, is also fundamentally about culture and approach. It describes the attitude of the startup community in Boulder, drawing broader lessons for other regions to learn from. Among these are inclusiveness, playing positive-sum games, being mentorship driven, having porous boundaries, and giving before you get, along with others.

“What we discovered is a community [in Boulder and Denver] full of ambitious leaders who value cooperation” ~ 5280 Magazine

I’m only a few of days in, but I can already see something is special here. Boulder may look like a small city (~108K residents), and it may act like a small city (people are very friendly and open), but it doesn’t feel like a small city—at least not like the small cities I have known. Boulder is an unmistakably vibrant place, with an army of smart, enthusiastic people doing interesting things, and having fun along the way.

Ok, but what’s this got to do with coffee?

After two days of driving to get here—some of it through poor, mountainous weather—my dog and I were a little on edge. To make matters worse, we had a bizarre run-in with a giant, angry cat upon arrival that left her quite shaken. Frankie is a very sensitive soul, and this series of events—the travel, the new environment, and the cat from hell—left her even more clingy to me than ever.

Saturday morning rolled around and I needed my coffee. The house I’m renting was empty of rations, so I ventured out to the local java establishment. Dogs are very much welcomed outside, as could easily be seen by the array of them on the sidewalk (one local said to me, “Welcome to the West Pearl Dog Park!”), but forbidden from going inside. Fair enough. But Frankie wasn’t having it. She was not ok with any sort of separation between us. How the hell was I going to get my coffee without further traumatizing her?

That’s when the community kicked in. Two tables of complete strangers sprung into action, offering to care for my distressed dog, putting her at ease so that I could grab a cup of joe. As these, and other valiant efforts failed, one kind neighbor emerged from inside, extending to me a hot cup of coffee, a sugar-laden pastry, and a warm smile. A chair was gently pushed out from one of the tables and Frankie and I were invited to join in Saturday morning conversation, as if we had done so many times before.

What became immediately obvious to me is that these people—a diverse bunch—know each other very well. They all live in the immediate neighborhood, had done so for many years, and they interacted frequently at their favorite neighborhood meetup. And yet, here they were, immediately welcoming a stranger into their world, sharing ideas and insights about the place they call home.

It was all there right in front of me, what I had come to learn about, contribute to, and be a part of—a community of established “leaders”, who were inclusive, cooperative, playing a positive sum game, giving before they received, and mentoring a newcomer. It was what I had heard about, but was experiencing first-hand in a totally unexpected way—which in my experience, is how some of the deepest learnings occur.

Things unfolded as they needed to, and I’m looking forward to the adventure ahead. I do it with eyes open, ready for my opportunity to pay it forward… as one does in a community.

Since I’m new, I’d love to get in touch. If you’re local and want to meetup, you can find me on Twitter or via email. Thanks in advance for the warm welcome. And, let me know how I can be of help.

What Can Startup Communities Do for Rural America?

Matt Helt, the director of Startup Week at Techstars has a great post up titled What Can Startup Communities Do for Rural America? I encourage you to read the whole post, but I’ll except a specific section about startup communities and rural America.

“First, it gives people the inspiration to develop the idea they’ve been working on in the back of their mind. It shows them there’s a path forward, and if done properly, can lead to real opportunity. All it takes is access to the internet. The internet has created a true egalitarian system that gives entrepreneurs access to customers anywhere in the world.

Second, startup communities share best practices and mentorship. Through shared learning, startup founders are much more likely to succeed and avoid the pitfalls others have experienced.

Third, communities that have strong startup ecosystems retain talent and attract outside investment. These dollars stay in the community and lead to business growth, which ultimately leads to job creation. The more businesses that are started, the more people are employed. (For examples, see the resources at the end of this post.)

The last point I’d like to make about startup ecosystems is that it requires the community to embrace radical inclusion. This means anyone who is interested in becoming an entrepreneur is welcome to take part. There can be no exclusion based on gender, race or socioeconomic status. All are welcome to take a seat at the table.”

If you are interested in engaging, reach out to me anytime and I’ll connect you up with the right folks.